I get this question frequently, how can I gain strength and not hurt my joints? It’s no secret that as most athletes age they transition from strength training to more cardio-based conditioning training or sports. Why do you think this occurs? I am not sure any of us know the exact reason, and if there is only ONE reason. I am convinced it is a multi-variate phenomena that occurs as we age. What are those variable you might ask?

In no particular order of importance, the potential reasons for why athletes avoid or reduce their strength training are…

1. Injury which limits strength training and prevents future interventions

2. Joint pain due to early or progressive degenerative changes of articular cartilage surfaces and connective tissues

3. A value based perception that strength training is dangerous and not appropriate for older athletes

4. Intuitive training modification due to a sense of self awareness from training based recovery symptoms

5. Advice from trainers

6. Cultural and social beliefs that predicate a sedentary existence

Even though there are probably a myriad of reasons why athletes back off of strength training as they age, CrossFitters defy this trend. Why? I believe the key is proper programming, mobility, recovery, nutrition and a thorough understanding of what strength movements have the greatest value and produce a solid rate of return. But, even in the CrossFit community, we see older athletes reducing strength training due to many of the reasons listed above.

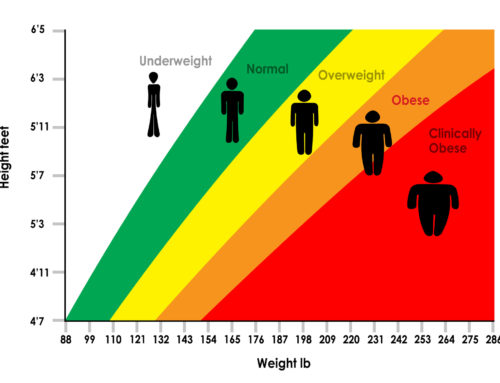

Is strength training important? Absolutely! It is probably the most important training intervention that masters athletes can participate in. Why? Out of all the 10 general physical skills, strength has the most rapid decline per decade and supports all the other physical skills. So, we need strength!

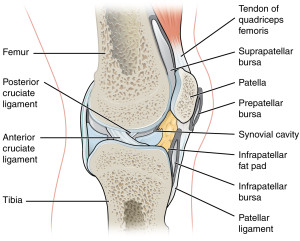

The one variable, that I see most often limits an athlete’s ability to continue strength training with loads that will maintain and grow lean mass, is joint pain. The problem is, once the joint starts hurting much of the damage is done. What we’re really talking about here is cartilage and connective tissue. The articular cartilage is the covering of the bone surfaces that allows for smooth gliding and the handling of compressive, rotational and shear loads. Articular cartilage has minimal to no blood supply to support transporting nutrients for function and healing. It also has poor nerve innervation limiting pain perception of the cartilage and thus the warning sign when the cartilage is being damaged. Cartilage relies almost entirely on anaerobic metabolism for the support of its viability. Tissue fluids represent 65-80% of the total weight of cartilage. Water is the most abundant component of articular cartilage contributing up to 80% of its weight. Cartilage relies on loads (weight bearing and movement) for its health, but when loads are applied in inappropriate forces or angles, the cartilage is at risk of damage.

So, how do we maintain or even increase strength and at the same time protect our joints? I don’t think there is one magic formula to accomplish this endeavor, but here are some practical thoughts that have worked for myself and athletes that I train.

1. Follow the progression of development advocated by CrossFit, Safety, Consistency, Intensity (proper form and movement should always precede loads and difficulty)

2. Develop the needed mobility in joints and connective tissue before Heavy loading. When mobility lacks, and there is poor quality movement, there are increased joint shear forces, inappropriate movement patterns and Noise during training. Noise? That’s right, Noise. Think of radio that the louder you turn it up, the more distortion there is. When movement is poor and loads are high, there is considerable neural noise which continues to support inappropriate movement patterns and thwart improvement. It’s common to see athletes in any training environment whether it be CrossFit, a globe gym, or even a client with a personal trainer, lifting too heavy without proper movement. Let’s face it, we all want to lift heavy! But going too heavy without proper movement puts your joints at greater risk than needed. Make mobility as important as strength training. Plain and simple, want to get stronger? Get more mobility to improve movement and protect your joints.

3. Follow proper training programming. In other words, rest, recover and support your strength training with nutrition, supplements, hydration and strength training volume that allows growth. Work major muscle group movements, back squat, deadlift, front squat, shoulder press, etc, utilizing a solid programming model such as Starting Strength. Listen to how your body adapts to the stimulus. Listen to your body and assess how many sessions a week of both strength and conditioning your body can take without a degradation in health and performance. Don’t just do, to do! This is a common mistake among athletes who lack direction in their program. Do, to gain health and performance. In general, I recommend 2-3 days of strength training and 2-3 days of conditioning at varying intensity levels. If you are a competitive or elite athlete, your competitive level will dictate volume.

4. Recognize that joints age and articular cartilage and connective tissue need rest from heavy loads but also require loads to maintain health. Older joints are not the same as younger joints, period! As a joints ages, the articular cartilage becomes less elastic, more dense and stiffer. There are also lower hydration levels. On the other hand, we know through research that a sedentary lifestyle actually causes cartilage health to decline and that regular application of normal daily and training loads helps to maintain cartilage health. It is the higher volume loading without adequate rest and recovery that can shift the balance from health to inflammation and then damage to the intracellular environment which can alter cartilage metabolism and cause injury. Once the pain in the joint is felt though, the damage is done!

5. Hydrate, hydrate, hydrate! Water and nothing else can adequately hydrate the extracellular matrix and tissues of joints. If you have inadequate hydration, you are not only limiting strength performance by 10-15% but you are also impairing recovery and joint health. Consume half you body weight lean mass in ounces of water per day at a minimum.(.5 x LMBW=ounces of water) On heavier training days with increased sweating, increase your hydration. Limit caffeine and other natural diuretics to healthy levels.

6. Once a base or foundation of strength is established, know how much is enough? I see this all the time, an athlete who is 45-50 years old with strength numbers through the roof, and their still performing 1 RM and pushing the limits. Hey, to each his own, but I think there does come a time in every athlete’s development where they have to ask themselves, “how much is enough?” I can’t answer this question. Athletes should pragmatically ask themselves how much strength is enough for function and performance? Once that foundation is built, strength can be maintained and even matured through lower loads (65-80%) and volume. Just remember, the closer you get to maximum capacity, the closer you get to tissue failure. Get greedy and you might end up on the wrong side of the sickness-wellness-fitness continuum. You be the judge.

The takeaway here is this, train but train smart. Recognize that strength training is the keystone to athletic development, graceful aging and performance. Start slow and ramp up to higher volume training in regards to frequency, loads, etc… Get a good trainer who understands your needs and the “biological” age of your body. Listen to your body!

Without Strength, the other 9 general physical skills don’t exist! But to strength train; and not to follow safe, consistent training principles, develop mobility, utilize proper programming, recognize that aging cartilage does have its limits, properly hydrate, and know your own strength limits, leads to joints that will eventually hurt and not allow loads to be lifted. No formula is full proof, but I have trained masters athletes at all levels that using these principles have been able to support function and performance.

Be healthy and go lift!

AJ Fox MSc, A Bedi MD, S Rodeo MD. The Basic Science of Articular Cartilage; Structure, Composition and Function. The Journal of Sports Health, Vol.1 No.6, Nov-Dec 2009.

Leave A Comment